EPISODE 163 FEATURES FASHION HISTORIAN RACHEL ELSPETH GROSS

What Can Fashion History Teach Us About Sustainability? Which fashion figures tower over the history books? Who’s fame stands the test of time, and who gets forgotten - and why? What can we learn from wartime rationing and the Make Do & Mend movement? How was life when home-sewing used to be the norm rather than exception? What new materials rocked the runways in the 1960s, and did disposable fashion originate with a faddish paper dress?

This week, we take a look at some of the sustainability angles and moral dilemmas from fashion history’s archives, with American fashion historian Rachel Elspeth Gross. It’s a conversation is full of intriguing stories from fashion’s past, that might help make sense of the present – or encourage us to look at it in new ways.

NOTES

ABOUT RACHEL Since September 18, 2018 fashion historian Rachel Elspeth Gross has run her popular blog, Today’s Inspiration, about the history of high-end fashion design. Her work has been featured in Women’s Wear Daily, the New York Times, Italian Harper’s Bazaar, and The National News; she has a column in The Vintage Woman magazine. In 2020 she began the Instagram Live series Couture Kibbitz with vintage fashion pioneer Cameron Silver. Find her website here, and on Instagram here.

Portrait courtesy Rachel Elspeth Gross

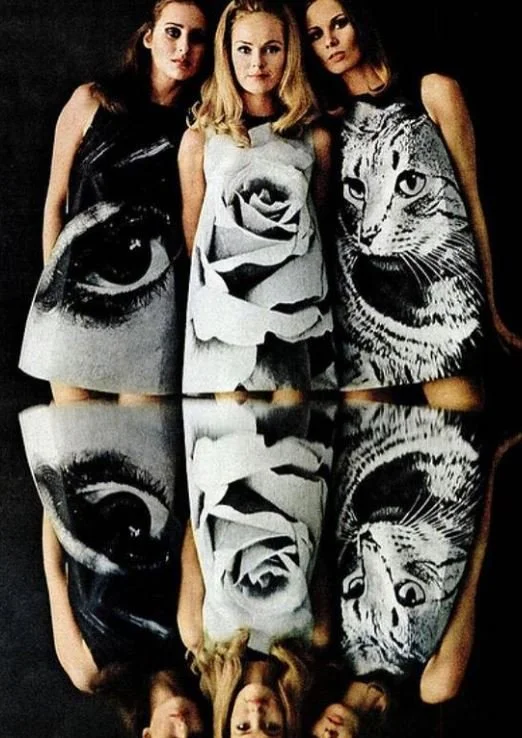

PAPER DRESSES were a 1960s fad, launched by a paper company as a marketing moment. Want to buy one today? Not easy given they were designed to throw away, you’ll have to pay big bucks. Here’s the cat face version - rare, unopened, on Etsy. A snip at $3,138.

Read the post.

It's an icon. The DIOR BAR JACKET is “an architectural work, virtuoso legend and the House’s stylistic emblem, sealed Christian Dior's success in 1947. A true ode to sensuality and desire, it alone symbolizes the revolution of the New Look. Reinterpreted by the House's various Artistic Directors, most recently by Maria Grazia Chiuri, this incomparable creation renews its timeless essence season after season with spirit and audacity.” Via Dior.com. Got a spare 7K? Buy yours here.

Read the post.

WARTIME AUSTERITY led to fabric and even button restrictions, when governments stepped in to limit things like the number of pleats in a skirt. Clothes were rationed in Britain from 1 June 1941. This limited the amount of new garments people could buy until 1949, four years after the war's end. “When Britain went to war in 1939 it seemingly spelt an end for fashion. The people of Britain now had more pressing concerns, such as widely expected air raids and possible German invasion. In many ways war did disrupt and dislocate fashion in Britain. Resources and raw materials for civilian clothing were limited. Prices rose and fashion staples such as silk were no longer available. Purchase tax and clothes rationing were introduced. But fashion survived and even flourished in wartime, often in unexpected ways…” via Imperial War Museums. Read the rest here.

ELEANOR LAMBERT “was a pioneer of the advocacy of American fashion. Her tireless efforts laid the groundwork for the recognition of New York as an international fashion capital. Her impact is still felt in the fashion industry as well as the culture at large. Today, designers are elevated to celebrity status and honored annually at the CFDA Awards.” Via FIT

THEATRE DE LA MODE was a 1945–1946 touring exhibit of fashion mannequins created at approximately 1/3 the size of human scale, and crafted by top Paris fashion designers. It was created to raise funds for war survivors and to help revive the French fashion industry in the aftermath of World War II.

Read the post.

PACO RABANNE was a Spanish fashion designer who shook up the 1960s fashion scene with his futurist vision. Rabanne had visions of another kind too. In his 1994 book, Has The Countdown Begun? book, he describes an incident from his (earthly) childhood: “I was lying on my bed, half asleep, at the age of seven. My spirit rose slowly from my inert body and I was suddenly transported into the presence of a strong light whose source I could not make out. I was no longer conscious of my own existence... Instinctively, I knew that I was on the Seventh Vibratory Plane, where everything is simply Essence. I no longer had bodily shape. I was a simple entity, vibratory and luminous..." More here.

Paco Rabanne designs 1966

DONYALE LUNA was a pioneering 1960s African-American model, the first woman of colour to appear on the covers of Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. A favourite of Richard Avedon and Andy Warhol, she also worked with Salvador Dali, Michelangelo Antonioni and Federico Fellini. Telegraph Fashion describes her as: “was the first Black model who really began to change things; to enable more diverse beauty paradigms to break through.” Read more on Vogue.

Read the post

KANSAI YAMAMOTO was a Japanese fashion designer well known for collaborating with David Bowie.

Read the post.

Vale ANDRE LEON TALLEY - a fashion king. Talley died in January 2022 leaving a legacy of fabulousness across the entire industry. Called “a creative genius,” he was the rare Black editor at the top of a field that was mostly white and notoriously elitist… Read his NYT obit here.

Read the post.

SEWING SKILLS used to be the norm not the exception. Hark back to the Halcyon days with the below book post.

Read the post.

EMILIE LOUISE FLOGES was an Austrian fashion designer. Here’s a great explainer from Harper’s Bazaar: “Before Coco Chanel There Was Emilie Flöge: A Designer the Fashion Industry Forgot. Gustav Klimt's muse was a fearless, trailblazing designer who inspired some of the 20th century's most iconic paintings…”

Read the post.

RATIONAL DRESS In mid-late-Victorian era (1850s-1890s), “People wanted to make clothing more practical and comfortable to use. The dress reformists were, mostly, middle-class women, first feminists in the US and UK. One of the main ideas …was to change the undergarments into more adequate ones that didn’t restrain movements of a person (first of all, woman). Though, male clothing also was influenced by these reforms – knitted wool union suits or ‘long johns’ became a widespread men’s underwear.

There were 5 main rules of the rational dress society:

freedom of movement;

absence of pressure over any part of the body;

not more weight than is necessary for warmth, and both weight and warmth evenly distributed;

grace and beauty combined with comfort and convenience;

not departing too conspicuously from the ordinary dress of the time.”

Via Amanda Hallay / nationalclothing.org